King of the Squirrels and Victor Hugo's Drawings

Cute rodents and the World's Greatest Author was also a pretty good artist!

"Instead of worrying about what you cannot control, shift your energy to what you can create."

— Roy T. Bennett (The Light in the Heart)

"Creativity is intelligence having fun."

— Albert Einstein

"The most regretful people on earth are those who felt the call to creative work, who felt their own creative power restive and uprising, and gave to it neither power nor time."

— Mary Oliver

I have a great-nephew! My father has his first great-grandchild. We drove about two hours to meet the little tyke. He’s adorable, tiny, still curved in that cute polywog shape. His eyes, I’m sure, will be blue, because both of his parents have beautiful sky blue and gray blue eyes. Maybe they will be the same light aqua color as my mother’s!

Dad and I were both so happy to finally hold him. My niece gave birth like a trooper two weeks ago. She was still glowing with love and hormones when we arrived on her doorstep. Her husband is about to head back to work after paternity leave, but the nursery is perfect, all accoutrements placed carefully around the house and the new mother is all set to enjoy six months of getting to know her new little buddy.

We had a few bittersweet moments among the joy. I hate that my mother did not live long enough to see him, but also take great comfort that she knew he was arriving and shared excited conversations with her granddaughter about his name, the physical changes of pregnancy and anticipation for the future family. She would have loved oohing and ahhing over his tiny hands and feet, his sweet face and funny, disgruntled expressions after he finished nursing. So - we all missed Mom, but I like that we were all thinking of her at different moments.

And, of course, her genes were right there, mixed in with the other three grandparents. My niece’s favorite movie as a three year old was The Lion King, and I felt like she should have had The Circle of Life song on repeat. Dad could have lifted him into the air in triumph. Hmm, missed a great photo opportunity there.

Oh well. I had some other good photo moments. I have taken on the role of Bird and Squirrel Whisperer. When we first arrived here to start our two month sojourn before leaving for Tasmania, the weather was frigid, the wind mean and frosty. I bought some bird seed from Walmart and filled up my mother’s bird feeder.

Then I realized the poor squirrels were hanging out on the deck waiting for the ravenous birds to knock some seeds off of the lip of the feeder. I decided to put out a plastic plate with a mound of seeds just for the squirrels. Rookie mistake.

We now have cardinals, tiny sparrows, some mourning doves, other little birds with a yellow throat, and three or four very boisterous squirrels. We also have a large hawk that likes to come and sit on the tree limb around the corner. Pretty sure we had more than four squirrels earlier this month, so I’ve also created a Circle of Life outside the dining room window. The hawk is pleased that I’ve enticed the local wildlife into one easy-to-manage location.

I let the plate run out of food a few days ago, and damned if the little rodents with long tails didn’t chew their way onto the screen porch and into the feed bag. Now I know why my Mom kept the seeds in a tupperware container. So now I’m checking the plate every day and making sure they have enough - a bribe to keep them from taking over the porch like a burgeoning squirrel mafia family.

The King has the best of all worlds. He’s figured out a way to climb the pole, hang on to the top of the feeder with his back feet and use his front paws to cram seeds into his mouth. No need to wait for the lazy human to put a plate out. The other lesser squirrels look on with jealousy and awe, getting so frustrated that they chase each other at mad speeds around the outside of our house while they wait for him to deign to drop a few in their direction.

Here’s Alfred making eye contact with the fearless King. Alfred is a bit perturbed that the squirrel does not fear his eleven pounds of pure feline muscle. I’m just happy that the squirrels and birds are keeping Alfred and Nyx entertained.

Make that, keeping US entertained. Note to self - buy a bird feeder upon arrival in Tasmania, you’ve got another winter coming down there. And the cats need to make friends with the locals.

(I have an attorney friend in Manhattan who takes pictures of tourists taking pictures of squirrels in Central Park. I hate that I am now counted among those gullible people he mocks. But squirrels ARE insanely entertaining. Not as cute as the red squirrels in Germany, but close.)

ANYWAY, on to the Art. I found this wonderful article in The Times - the British version, not New York. I absolutely LOVE this paper. I only read it online now, but when I was stationed at SHAPE-NATO in Mons, Belgium, I’d get up early on the weekend, drive into the NAAFI onpost and buy the physical version, all ten pounds of it. (Well, I exaggerate, but it was a big, thick paper!) Multiple sections and magazines - travel, opinion, style, theatre, books.

I’d rush back home, make a huge pot of coffee, load up a plate of croissants with butter and spend about two hours on the living room floor - back against the sofa, paper to my left, reading each section then happily tossing them into a messy pile on my right. Once I’d completely educated myself with all of the current events, I’d take a carb coma nap for about an hour, then head over to the PX in Schinnen for my weekly grocery shop. Good times.

My favorite section now? The obituaries. They are beautifully written, and cover all walks of life - WWII heroes, actresses, scientists, writers, even charitable people without a lot of money or fame. It’s like a tiny little jewel of current history every morning with my tea. The travel section makes me melancholy these days - I can no longer easily get to those 10 Best, Cheap Hotspots in Estonia. The bargain travel is a bargain when you live on the continent, not so much from North Georgia or Tasmania.

Here’s The Times webpage if you’d like to subscribe and get away from our more divisive state side version of the news. It’s not very expensive, and worth every penny. (Geez, I guess now that pennies are going away, we’ll have to come up with new phrases. A nickel saved is a nickel earned. Worth every dime. See a quarter, pick it up, all day long you’ll have good luck. Hmm. Missing something, isn’t it?)

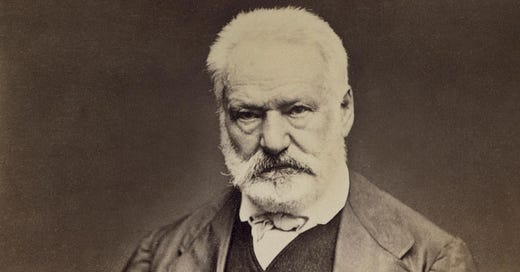

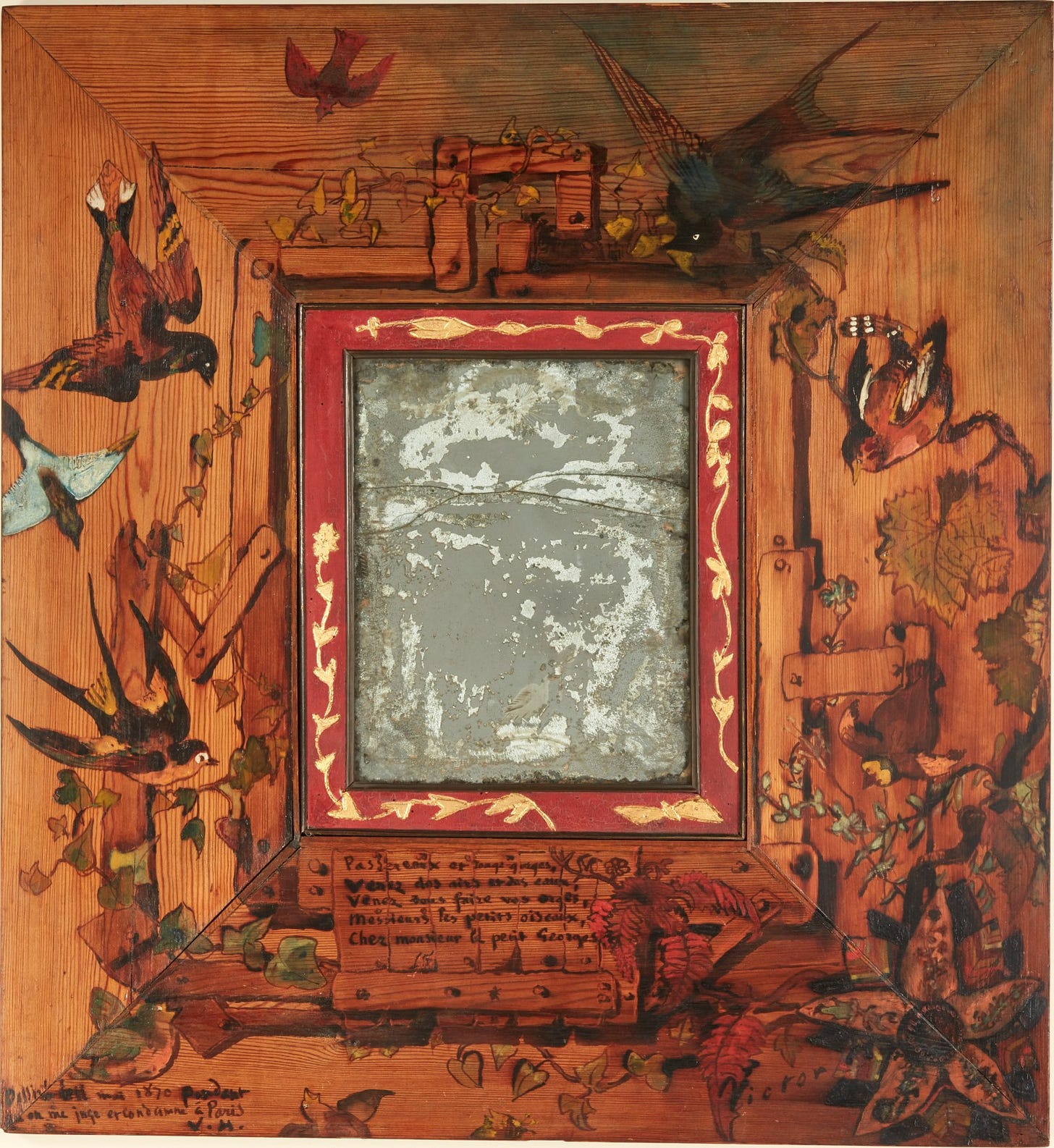

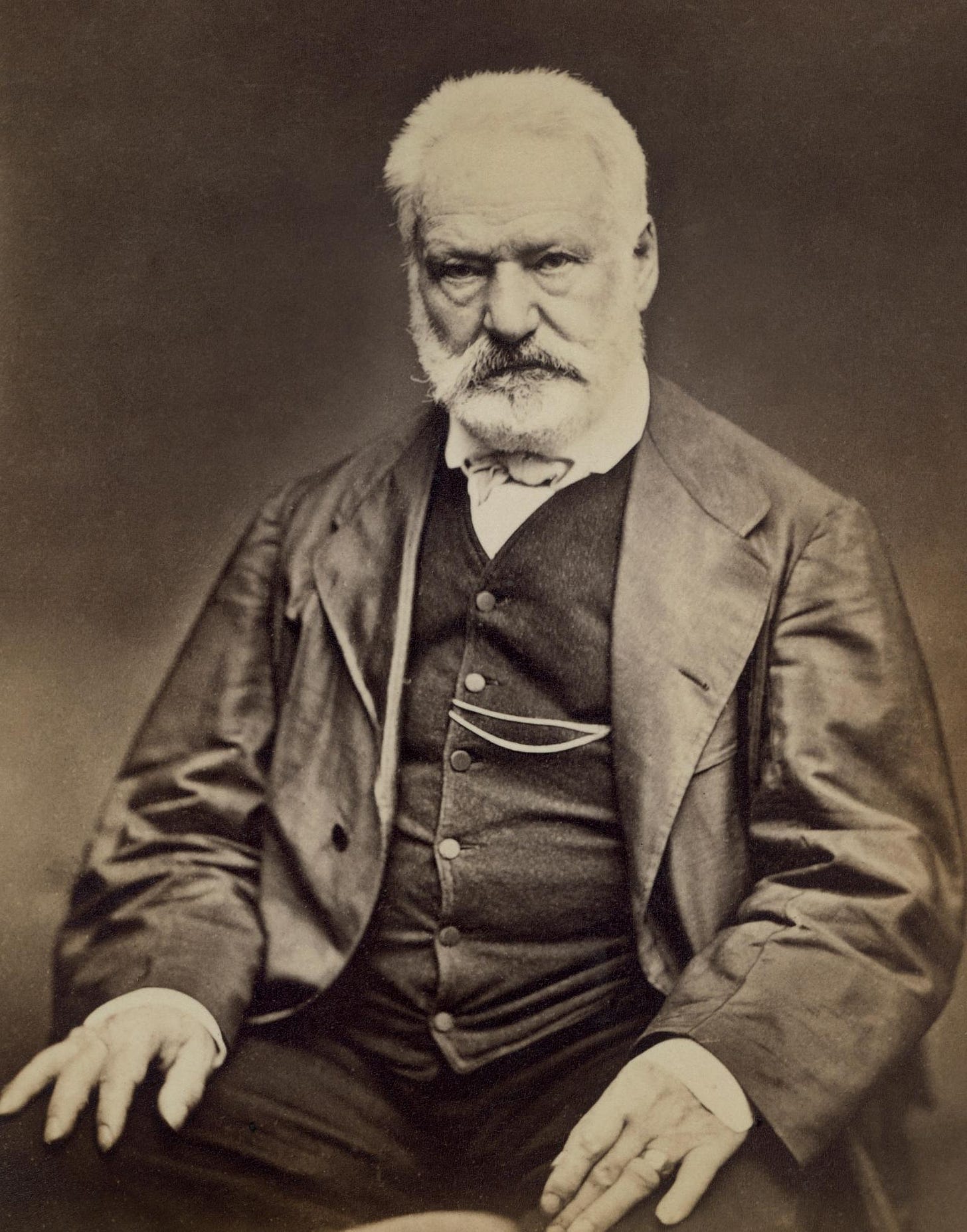

Earlier this week, The Times provided a great education on writers who also draw, with specific attention paid to the great Victor Hugo as subject of an upcoming exhibition of his drawings. If you are planning a trip to London in the near future, you might want to swing by and check out Astonishing Things: The Drawings of Victor Hugo at the Royal Academy, London, Mar 21-Jun 29. Looks like I’ll miss this one, so I’m glad that Rachel Campbell-Johnston spent so much time writing down all the details.

When Victor Hugo died in Paris in 1885, his was among the most recognised names in the world. About two million mourners (and presumably curious gawpers) followed his funeral procession from the Arc de Triomphe to a tomb in the Pantheon. There, his body was laid to rest. But his reputation lived on, not least through the musical adaptation of Les Misérables, which has been seen by more than 130 million people in 53 countries and performed in 22 languages. It also holds the record for the longest-running West End musical, with more than 15,000 performances.

This year, however, as Cameron Mackintosh’s production of Les Mis celebrates its 40th anniversary, the Royal Academy introduces audiences to a lesser-known aspect of Hugo’s creative talent. This literary giant was also an accomplished draughtsman, as Astonishing Things: The Drawings of Victor Hugo will demonstrate.

Hugo’s drawings were never exhibited in his lifetime. He was dismissive of them. He was an artist “in spite of himself”, he declared. He drew to relax, record scenes from his travels, illustrate letters and entertain his children or friends. But what had started as a hobby came to have greater significance, most particularly in those years between 1848 and 1851 when, after giving up writing to devote his attention to politics, drawing became his only creative outlet.

He was prolific. About 4,000 drawings survive. From these, the Royal Academy has selected about 70 of the finest for display. They range from Hugo’s most grandly ambitious composition, The Castle with the Cross (represented by a print), to tiny sketches the size of a postage stamp; from fantastical castles that conjure up a quintessentially Romantic aesthetic to a macabre figure dangling from the gallows that manifests its creator’s repulsion for the death penalty.

Seen together in this exhibition, the first of Hugo’s artworks to come to Britain in 50 years, they reveal a talent worthy of being written into the history of art. Not least because, a century before the surrealists made it fashionable, Hugo incorporated stains and ink blots as well as found materials — coffee, soot or greasepaint — into his pictures, using rags, sticks and stones to create effects.

Hugo, however, is just one, albeit one of the most talented, of the many celebrated authors who have moved between manuscript and sketchbook. “It’s just perfectly ordinary,” Kurt Vonnegut declared. “I mean I might have been a writer and a golfer too.” There was no essential difference between word and image, Colette suggested. “For half a century I wrote in black on white, and now for nearly ten years I have been writing in colour on canvas.” Drawing, Jean Cocteau declared, was just “a different way of typing up lines”.

Perhaps it’s hardly surprising. Are drawing and writing really that divided? In just a flick of the wrist, the wordsmith can slip into daydreaming doodles, although it’s a rather bigger jump for the keypad typist.

Several of our greatest writers began their creative trajectories as artists. As a teenage apprentice to a rural architect, Thomas Hardy was set to drawing churches. Henrik Ibsen first trained in a painter’s studio. Gunter Grass studied sculpture. GK Chesterton enrolled at the Slade School of Art in 1892. Max Beerbohm, from childhood, was a committed self-taught painter while Edgar Allan Poe covered the walls of his student digs with his caricatures. Others discovered art later. In the last four years of his life, DH Lawrence found himself to his astonishment “bursting into paint”.

August Strindberg described his first experience of painting as being like a hashish high. “It steeps me in a sacred rapture to see a portrait develop and take soul under my hand,” declared the more characteristically acerbic Mark Twain.

A picture is worth a thousand words, goes the adage. How that must taunt the writer. “Language is intrinsically approximate,” John Updike said. But when he drew a line, he declared, it was “exactly as I made it”. Little wonder that several writers have experimented with calligraphic patterns. Poets from Simmias of Rhodes to the metaphysical George Herbert, the symbolist Guillaume Apollinaire to the contemporary concrete poet Ian Hamilton Finlay, have played about with calligrams, turning words into art.

On the flipside are those who translate images to language. Mikhail Lermontov, in his bid to evoke the spirit of wild Russian landscapes, referred to his aide-memoire sketchbooks. Fyodor Dostoevsky’s manuscripts are scattered with the little pen-and-ink faces that helped him to visualise his characters’ physiognomies. Drawing shaped the writing of Sylvia Plath, transforming intellectual understanding into physical experience, she explained.

Word and image elide most obviously in illustration. Pictures offer a sort of simultaneous translation of text. Medieval manuscripts entice with their narrative pictorials. William Blake’s glowing images illuminate his poems. Lewis Carroll, huddling up with his eager young listeners, would draw lightning-quick sketches as his stories rolled off his tongue. RM Ballantyne, who illustrated dozens of his novels, grounded extravagant fictions in the reality of meticulous drawings. William Makepeace Thackeray’s sharp caricatures comment ironically on the novelistic characters whom he creates.

Forms of expression may differ, but the underpinning emotion is frequently the same. You can recognise Nikolai Gogol’s baroque spirit, Lawrence’s erotic compulsions, David Jones’s nervy jittering or Vonnegut’s black humour as much in their visual images as in their written work. Other authors seek through their drawings to express that which their writing cannot quite reach. “A large part of man,” wrote Rabindranath Tagore, who turned to painting in old age, “can never find its expression in the mere language of words.”

In their discovery of an alternative discipline, authors may reveal aspects of character that they otherwise don’t expose. Who would guess that Hermann Hesse, that untiring prober of human psychology, would depict sunny landscapes; that the trouble-worn Joseph Conrad would sketch frothy-skirted can-can dancers; that Edward Lear, so famed for his silly limericks, would be a serious landscapist? Charles Kingsley, a Church of England parson and chaplain to Queen Victoria, let his sexual fantasies free in little ink sketches, while the hellraiser Arthur Rimbaud, who would hop up on to the dinner table to defecate, produces surprisingly tame little doodles.

For Eugène Ionesco art was a rescue from writer’s block and for Hesse a path back from despair. “I would have long since given up living if my first attempts at painting had not comforted and saved me,” he wrote.

The visual and the textual work in very different ways. Grass, whose fetishistic graphics accompanied many of his novels, sums up the relationship: “Look, says the image, at how few words I need. Listen, says the poem, to what you can read between the lines.”

Yet the “itch to make dark marks on white paper” as Updike put it, is shared by many artists and writers. The urge arises from a fundamental spirit of creativity, “that supreme aliveness” described by ee cummings, who painted, he said, “for the same reason I breathe”. Franz Kafka declared: “My drawing is a perpetually renewed … attempt at primitive magic.” He was not very good at it and readily admitted as much, but he, like so many of his fellow writer-artists, was compelled by the power of a creative force as primal as those pictographic symbols our ancestors first felt impelled to scratch on rocks.

I am in good company. My easel is packed, along with my paints and brushes, but I’m letting loose a little creativity every now and then by writing on Substack and finding great art to share. I’m not Victor Hugo, by any stretch, but I get the compulsion to stretch a bit.

Glad nature’s little clowns are entertaining you. They are fun and exasperating 😉. Congratulations on the Boyd family’s precious new addition. Maybe he’ll be a world traveler like his great-auntie.

Sure will miss sharing a continent but excited for your new adventures 🥂